Advanced Mobile Malware Campaign in India uses Malicious MDM - Part 2

0.972 High

EPSS

Percentile

99.8%

This blog post is authored by Warren Mercer and Paul Rascagneres and Andrew Williams.

Summary

Since our initial post on malicious mobile device management (MDM) platforms, we have gathered more information about this actor that we believe shows it is part of a broader campaign targeting multiple platforms. These new targets include Windows devices and additional backdoored iOS applications. We also believe we have associated this actor with a very similar campaign affecting Android devices.

With this additional information, we have been able to build a profile of how the MDM was working, as explained in the previous post, while also allowing us to identify new infrastructure. We feel that it is critical that users are aware of this attack method, as well-funded actors will continue to utilize MDMs to carry out their campaigns. To be infected by this kind of malware, a user needs to enroll their device, which means they should be on the lookout at all times to avoid accidental enrollment.

In the new MDM we discovered, the actor changed some of their infrastructure in an attempt to improve the MDM’s security posture. We also found additional compromised devices, which were again located in India, with one even using the same phone number linking the MDM platforms, and one located in Qatar. We believe this newer version was used from January to March 2018. Similar to the previous MDM, we were able to identify the IPA files the attacker was using to compromise iOS devices. Additionally, we discovered that malicious apps such as WhatsApp had new malicious methods tacked onto them.

During this ongoing analysis, we also looked into other potential indicators that would point us toward the actor. We discovered this Bellingcat article that potentially links this actor to one they dubbed “Bahamut,” an advanced actor who was previously targeting Android devices. Bahamut shared a domain name with one of the malicious iOS applications mentioned in our previous post. There was also a separate post from Amnesty International discussing a similar actor that used similar spear-phishing techniques to Bahamut. However, Cisco Talos did not find any spear phishing associated with this campaign. We will discuss some links and potential overlapping with these campaigns below.

New MDM

Technical information about the MDM

Talos identified a third MDM server that we believe was used by this actor: ios-update-whatsapp[.]com.

The first relevant difference between this MDM and the MDM we discussed in the previous article is the fact that the attackers patched the open-source project mdm-server — a small iOS MDM server. The attackers added an authentication process. In the last version, no authentication was available. Here is the auth page:

Additionally, we identified different technical information based on the certificate used. Here is the certificate used by this MDM:

CA.crt

Serial Number: 17948952500637370160 (0xf9177d33a2d98730)

Signature Algorithm: sha256WithRSAEncryption

Issuer: C=HK, ST=Kwun Tong, L=6/F 105 Wai Yip St 000000, O=TECHBIG, OU=IT, CN=TECHBIG.COM/[email protected]

Validity

Not Before: Jan 15 09:47:15 2018 GMT

Not After : Jan 15 09:47:15 2019 GMT

Subject: C=HK, ST=Kwun Tong, L=6/F 105 Wai Yip St 000000, O=TECHBIG, OU=IT, CN=TECHBIG.COM/[email protected]

A fake company, Tech Big, which was allegedly located in Hong Kong, had this certificate issued to it in January 2018.

Log analysis

Three devices were enrolled on this server:

- Two devices with an Indian phone number that were also located in India (one of the devices has the same phone number as the believed attacker’s device used in the previous post)

- One device with a British phone number located in Qatar

The logs showed us that the MDM was created in January 2018, and was used from January to March of this year.

New malicious iOS apps

Fake Telegram & WhatsApp

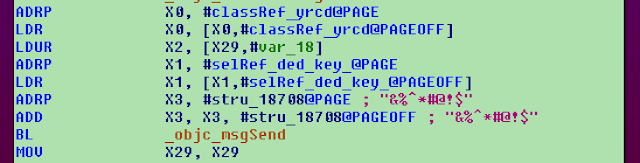

Talos identified two other malicious Telegram and WhatsApp apps. The attacker built these apps by adding malicious capabilities to existing Telegram and WhatsApp applications. The malicious aspect of the apps is the same as what we described in the previous post. The only difference is the command and control (C2) obfuscation. The URLs are not stored in plaintext, but are encrypted with data encryption standard (DES) and encoded in base64.

Here is an example of the encoded URL:

And the DES key:

Once decoded and decrypted, we can easily read the URL of the C2:

./decode.py vZVI2iNWGCxO+FV6g46LZ8Sdg7YOLirR/BmfykogvcLhVPjqlJ4jsQ== '&%^*#@!$'

hxxp://hytechmart[.]com/UcSmCMbYECELdbe/

Fake IMO

IMO is a chat and video app available on mobile devices. We identified a fake application that pretended to be IMO. The attackers used the same technique to add malicious code to the legitimate application: BOptions sideloading technique. For more information about this technique, we recommend reading the previous blog post.

The C2 server has the same obfuscation technique as the fake, malicious Telegram and WhatsApp apps described above. The attacker simply changed the encryption key used. The purpose of the malicious code is similar to the previous malicious apps in that it steals contact information and chat history. This application uses SQLite to store the data. Here is an example of request performed to get the data:

- DBManager accesses ‘IMODb2.sqlite’

- Select ZIMOCHATMSG.Z_PK,ZIMOCHATMSG.ZTEXT,ZIMOCHATMSG.ZISSENT,ZIMOCONTACT.ZPHONE,ZIMOCONTACT.ZBUID AS Contact_ID from ZIMOCONTACT join ZIMOCHATMSG ON (ZIMOCONTACT.ZBUID = ZIMOCHATMSG.ZBUID) where ZIMOCHATMSG.Z_PK >‘%d’

Malicious Safari browser

Talos has also discovered a malicious Safari application available on the third malicious MDM. For this application, the attackers did not use the BOptions sideloading technique. It’s a malicious browser developed from scratch and based on three open-source projects: SCSafariPageController, SCPageViewController and SCScrollView.

The purpose of this browser is to steal sensitive information from the infected device. First, the app sends the universally unique identifier (UUID) of the device to the C2 server. Based on the server response, the malicious browser will send additional information, such as the user’s contact information (picture, name, email, postal address, etc.), the user’s pictures, the browser’s cookies and the clipboard.

The malware checks for a file named “hib.txt,” and if the file doesn’t exist on the device, it displays an iTunes login page in an attempt to harvest the user’s login credentials. Upon entering the credentials, the email address and password are sent to the C2 server. Additionally, these credentials get written into the file and the user is considered “signed in.”

The most intriguing part is the credential stealer. If the browsed domain name contains one of the following strings, the malware will automatically exfiltrate the username and the password of the user to the C2 server. Most notably, there is the presence of secure email providers, among a variety of other web services.

- Login.yahoo (email platform)

- Mail.com (email platform)

- Rediff (Indian news portal and email platform with around 95 million registered users)

- Amazon (e-commerce platform)

- Pinterest (image-sharing and discovery platform)

- Reddit (news aggregation web portal with forums)

- Accounts.google (Google sign-in platform)

- Ask.fm (anonymous decentralised Q&A platform)

- Mail.qq (Chinese email platform)

- Baidu.com (Chinese search engine and email provider)

- Mail.protonmail (secure email provider located in Switzerland)

- Gmx (email platform)

- AonLine.aon (British assurance)

- ZoHo (Indian email service)

- Tutanota (secure email provider located in Germany)

- Lycos.com (search engine and web portal with email platform)

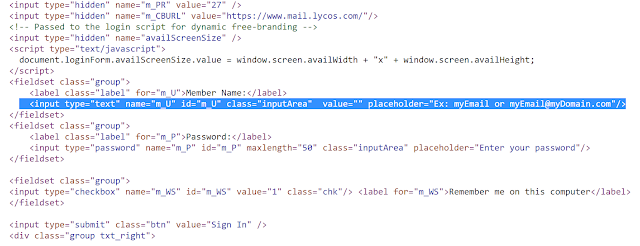

The malware continuously monitors a web page, seeking out the HTML form fields that hold the username and password as the user types them in to steal credentials. The names of the inspected HTML fields are embedded into the app alongside the domain names. Here is a list of the “username” fields that are referenced by the app code:

For example, we see m_U, which is the username field in the Lycos mail authentication page:

The malware contains a similar list concerning the password field.

Finally, the malicious browser contains three malicious plugins:

- “Add Bookmark”

- “Add To Favourites”

- “Add to Reading List”

The purpose of the malicious extensions are very similar to the previous ones — it sends off stored data to the same C2 server as the other apps.

In the core and the plugins, the C2 server is encoded in base64 and encrypted in AES instead of DES.

Links with previous campaign

The Bahamut group was discovered and detailed by Bellingcat, an open-source news website. In this post, the author was discussing Android-based malware with some similarities to the iOS malware we identified. That post kickstarted our investigation into any potential overlap between these campaigns and how they are potentially linked.

The new MDM platform we identified has similar victimology with Middle Eastern targets, namely Qatar, using a U.K. mobile number issued from LycaMobile. Bahamut targeted similar Qatar-based individuals during their campaign.

We identified an overlap in the domain voguextra[.]com, which was used by Bahamut within their “Devoted To Humanity” app to host an image file and as C2 server by the PrayTime iOS app mentioned in our first post. Bellingcat also reported the domain had been used previously to host potential decoy documents as detailed in VirusTotal here using hxxp://voguextra[.]com/decoy.doc.

The domains used during this campaign shared similarities with the domains used throughout the Bahamut campaign reported by Bellingcat. Most of the email addresses used within the domains were *@mail.ru email accounts, the C2s identified both used AES encrypted strings represented as base64 values, and the URI patterns used in both campaigns shared an almost identical syntax:

repository + random.php + GET value

/hdhfdhffjvfjd/gfdhghfdjhvbdfhj.php?p=1&g=[string]&v=N/A&s=[string]&t=[string]

The domains also had similar structures for the domain name (they are formatted [word]-[word]-[word]) across both campaigns. Actors tend to stick with similar structures, especially if they have had success in the past.

Once we started profiling the domains, we quickly noticed a strong link to India. With access to historical whois and hosting information, we were able to determine that the three MDM domains pointed to an Indian nexus. All three domains used a privacy proxy to register their domains. However, what the actor did not do was create nameservers upon registering the domains. This allowed us to discover that two of the three domains were registered with Indian registrars and hosting providers.

The three domains identified for MDM use were ios-update-whatsapp[.]com, ios-certificate-update[.]com and www[.]wpitcher[.]com.

ios-update-whatsapp[.]com

The nameserver used initially was obox.dns[.]com, which is owned by the India-based Directi platform, is an Indian registrar and was the original nameservers used by this domain. This later changed to being [ns1-2].ios-update-whatsapp[.]com, which suggests this domain was potentially registered and purchased in India.

wpitcher[.]com

This domain initially used nameservers related to the Indian company MantraGrid, an India-based cloud platform that shows another link to an Indian actor by using this as one of the original MDM domains we identified.

This domain used a similar structure to ios-update-whatsapp[.]com and also shared the same privacy proxy as the other two domains listed above relating to the MDM activity. This was one of the first registered domains and was using a bulletproof hosting platform in Panama.

Finally, Bellingcat, via Tom Lancaster, identified similarities with a previous InPage campaign reported by Kaspersky which shows similar URI structuring, as well as victimology. The InPage attack targeted Urdu-speaking Muslims, which further increases the likelihood that the victims are Indian-based because Urdu is a dialect primarily spoken in India and Pakistan. With our attacker, we identified that the MDM was also taking advantage of an application called PrayTime — a popular app for Muslims that alerts them to complete their daily prayers.

With all of this taken into consideration, we assess with moderate confidence that the attacker is located in India. Additionally, we assess with low confidence that the campaign we discovered is linked to the Bahamut group.

Links with Windows-targeted campaigns

Talos identified several malicious binaries that could be used to target victims running Microsoft Windows operating systems using the same infrastructure as the malicious app mentioned in our previous article, techwach.com.

The sample 6b62f4db64edf7edd648c38a563f44b656b0f6ad9a0e4e97f93cf9abfdfc63e5 contacts the following URL to download an additional payload from the following page:

- hxxp://techwach[.]com/Beastwithtwobacks/Barkingupthewrongtree.php

We know that the MDM and the Windows services were up and running on the same C2 server in May 2018. The purpose of this malicious Windows binary is to get information on the infected device (username and hostname), send this information and retrieve an additional PE32 file if the operator estimates that the targeted system is relevant.

We found additional similar samples between June 2017 and June 2018 with different C2 servers. The attackers have two kinds of samples: one developed in Delphi and one developed in VisualBasic.

Here are the Delphi samples:

- b96fc53f321729eda24af2a0b95e5c1d39d46acbd5a565e6c5f8c81f1bf9c7a1 -> hxxp://appswonder[.]info

- 3f463cebef1550b055ef6b4d1dad16ff1cb514f0091271ce92549e77bb5080d6 -> hxxp://referfile[.]com

- 4b94b152293e49532e549b2538cad85e950cd16ccd948a47a632376a840626ed -> hxxp://hiltrox[.]com

- e70a1c230ef2894363b834132bbdbb3a0edc88e81049a7c7774fa5b4ed78206b -> hxxp://scrollayer[.]com

- e7701f81141dfd6234488e51340ba2d05901c8242a6e9a9952c297c52a3ff050 -> hxxp://twitck[.]com

- e93f28efc1787ed5e8763cdc0417e7d5db1c9203e484350c64860fff91dab4f5 -> hxxp://scrollayer[.]com

Here are the VisualBasic samples:

- 6f362bc439ce09c7dcb0ac5cce84b81914b9dd1e9969cae8b570ade3af1cea3d -> hxxp://32player[.]com

- ce0026e0eb3f4f1d3d2a003400f863900f497745f3384e430926d99206cc5ed6 -> hxxp://nfinx[.]info

- d2c15c2043b0455cfad36f22f564b99ed46cea3891abb80eaf86093654c94dea -> hxxp://metclix[.]com/

- d7f90e9b1129e3223a886422b3625399d52913dcc2757734a67422ac905683f7 -> hxxp://appswonder[.]info/

ec973e4319f5a9e8e9c28d315e7bb8153a620baa8ae52b455b68400612aad1d1 -> hxxp://capsnit[.]com/

Some of the C2 servers are still up and running at this time. The Apache setup is very specific, and perfectly matched the Apache setup of the malicious IPA apps.

Additionally, we identified the infection vector of one of the Windows malware. The attackers used a malicious RTF (a1f2018bd61989a78247df53d808b6b513d530c47b89f2a919c59c848e2a6ac4) abusing the CVE-2018-0802 vulnerability in order to drop and execute the last binary of the previously mentioned list.

Finally, one of the VisualBasic binary was bundled in a msiexec file with this following decoy document:

This decoy document is using a news story image found on the India Today newspaper website here, which is describing the Naga peace accord. The Indian targets in this campaign are likely very interested in this topic.

Conclusion

Since researching our original blog post, we have discovered that an actor has been operating these malicious MDMs for many years. Based on previous research regarding the Bahamut group and our research, we believe the observed infrastructure is not limited to iOS targets, but is part of a broader framework that supports Apple iOS and Windows platforms.

This actor is likely located in India, given what we see in the technical elements. While the attacker’s infrastructure throughout the entirety of the operation seems very similar to the one used by the Bahamut group, and they may even be connected, it is not possible to assert with high confidence that it is Bahamut at this time.

The use of a malicious MDM is convenient and the system is well-documented. Given the effectiveness of MDM abuse, it’s likely that well-funded actors will continue to move into this area.

Because enrollment into the MDM requires user interaction and acceptance, it is crucial that they are aware of this type of threat and the dangers it can pose to their data and privacy.

Talos will continue to keep an eye on MDM and similar infrastructures to ensure we are reporting the latest information and forcing the bad guys to innovate.

Coverage

Additional ways our customers can detect and block this threat are listed below.

Advanced Malware Protection (AMP) is ideally suited to prevent the execution of the malware used by these threat actors.

Cisco Cloud Web Security (CWS) or Web Security Appliance (WSA) web scanning prevents access to malicious websites and detects malware used in these attacks.

Email Security can block malicious emails sent by threat actors as part of their campaign.

Network Security appliances such as Next-Generation Firewall (NGFW), Next-Generation Intrusion Prevention System (NGIPS), and Meraki MX can detect malicious activity associated with this threat.

AMP Threat Grid helps identify malicious binaries and build protection for all Cisco Security products.

Umbrella, our secure internet gateway (SIG), blocks users from connecting to malicious domains, IPs, and URLs, whether users are on or off the corporate network.

Open Source Snort Subscriber Rule Set customers can stay up to date by downloading the latest rule pack available for purchase on Snort.org.

IOCs

iOS Applications

- 422e4857614cc603f2388eb9a6b7bbe16d45b9fd0a9b752f02c107887cf8cb3e imo.ipa

- e3ceec8676e2a1779b8289e341874209a448b11f3d81834a2faae9c494267602 Safari.ipa

- bab7f61ed0f2b085c02ff1e4305ceab4479455d7b4cfba0a018b73ee955fcb51 Telegram.ipa

- fbfaed75aa855c7db486edee15359b9f8c1b394b0b02f77b22500a90c53cb423 WhatsApp.ipa

MDM Domain:

- ios-update-whatsapp[.]com

C2 Domains:

- hytechmart[.]com

PE32 Samples:

- b96fc53f321729eda24af2a0b95e5c1d39d46acbd5a565e6c5f8c81f1bf9c7a1

- 3f463cebef1550b055ef6b4d1dad16ff1cb514f0091271ce92549e77bb5080d6

- 4b94b152293e49532e549b2538cad85e950cd16ccd948a47a632376a840626ed

- e70a1c230ef2894363b834132bbdbb3a0edc88e81049a7c7774fa5b4ed78206b

- e7701f81141dfd6234488e51340ba2d05901c8242a6e9a9952c297c52a3ff050

- e93f28efc1787ed5e8763cdc0417e7d5db1c9203e484350c64860fff91dab4f5

- 6f362bc439ce09c7dcb0ac5cce84b81914b9dd1e9969cae8b570ade3af1cea3d

- ce0026e0eb3f4f1d3d2a003400f863900f497745f3384e430926d99206cc5ed6

- d2c15c2043b0455cfad36f22f564b99ed46cea3891abb80eaf86093654c94dea

- d7f90e9b1129e3223a886422b3625399d52913dcc2757734a67422ac905683f7

- ec973e4319f5a9e8e9c28d315e7bb8153a620baa8ae52b455b68400612aad1d1

PE32 C2 servers:

- hxxp://appswonder[.]info

- hxxp://referfile[.]com

- hxxp://hiltrox[.]com

- hxxp://scrollayer[.]com

- hxxp://twitck[.]com

- hxxp://scrollayer[.]com

- hxxp://32player[.]com

- hxxp://nfinx[.]info

- hxxp://metclix[.]com/

- hxxp://capsnit[.]com/

Malicious RTF Samples:

- a1f2018bd61989a78247df53d808b6b513d530c47b89f2a919c59c848e2a6ac4