McAfee ATR Analyzes Sodinokibi aka REvil Ransomware-as-a-Service - What The Code Tells Us

7.7 High

AI Score

Confidence

High

McAfee ATR Analyzes Sodinokibi aka REvil Ransomware-as-a-Service – What The Code Tells Us

By McAfee Labs · October 2, 2019

Episode 1: What the Code Tells Us

McAfee’s Advanced Threat Research team (ATR) observed a new ransomware family in the wild, dubbed Sodinokibi (or REvil), at the end of April 2019. Around this same time, the GandCrab ransomware crew announced they would shut down their operations. Coincidence? Or is there more to the story?

In this series of blogs, we share fresh analysis of Sodinokibi and its connections to GandCrab, with new insights gleaned exclusively from McAfee ATR’s in-depth and extensive research.

- Episode 1: What the Code Tells Us

- Episode 2: The All-Stars

- Episode 3: Follow the Money

- Episode 4: Crescendo

In this first instalment we share our extensive malware and post-infection analysis and visualize exactly how big the Sodinokibi campaign is.

Background

Since its arrival in April 2019, it has become very clear that the new kid in town, “Sodinokibi” or “REvil” is a serious threat. The name Sodinokibi was discovered in the hash ccfde149220e87e97198c23fb8115d5a where ‘Sodinokibi.exe’ was mentioned as the internal file name; it is also known by the name of REvil.

At first, Sodinokibi ransomware was observed propagating itself by exploiting a vulnerability in Oracle’s WebLogic server. However, similar to some other ransomware families, Sodinokibi is what we call a Ransomware-as-a-Service (RaaS), where a group of people maintain the code and another group, known as affiliates, spread the ransomware.

This model allows affiliates to distribute the ransomware any way they like. Some affiliates prefer mass-spread attacks using phishing-campaigns and exploit-kits, where other affiliates adopt a more targeted approach by brute-forcing RDP access and uploading tools and scripts to gain more rights and execute the ransomware in the internal network of a victim. We have investigated several campaigns spreading Sodinokibi, most of which had different modus operandi but we did notice many started with a breach of an RDP server.

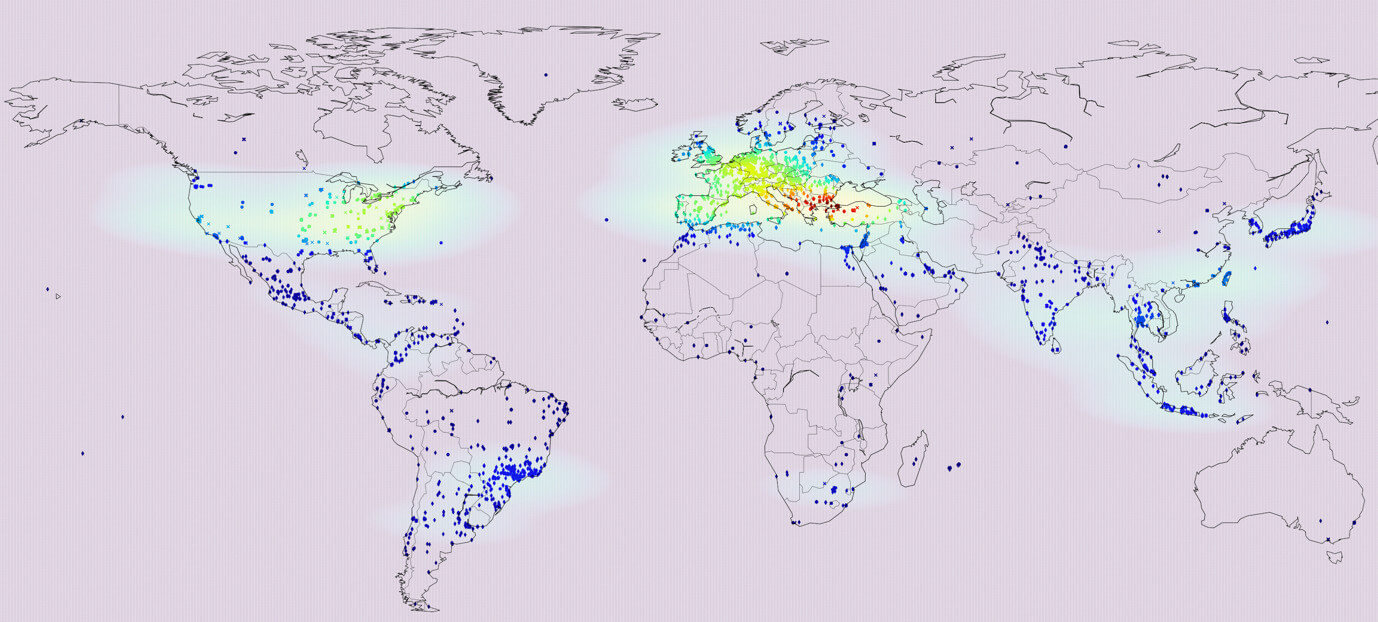

Who and Where is Sodinokibi Hitting?

Based on visibility from MVISION Insights we were able to generate the below picture of infections observed from May through August 23rd, 2019:

Who is the target? Mostly organizations, though it really depends on the skills and expertise from the different affiliate groups on who, and in which geo, they operate.

Reversing the Code

In this first episode, we will dig into the code and explain the inner workings of the ransomware once it has executed on the victim’s machine.

Overall the code is very well written and designed to execute quickly to encrypt the defined files in the configuration of the ransomware. The embedded configuration file has some interesting options which we will highlight further in this article.

Based on the code comparison analysis we conducted between GandCrab and Sodinokibi we consider it a likely hypothesis that the people behind the Sodinokibi ransomware may have some type of relationship with the GandCrab crew.

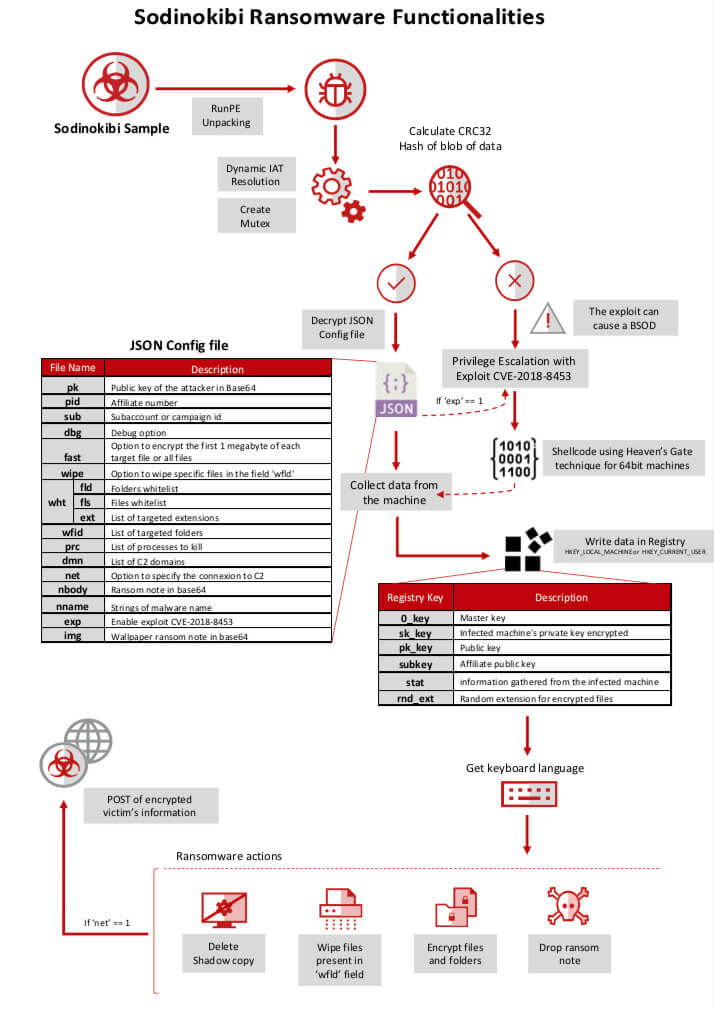

FIGURE 1.1. OVERVIEW OF SODINOKIBI’S EXECUTION FLAW

FIGURE 1.1. OVERVIEW OF SODINOKIBI’S EXECUTION FLAW

Inside the Code

Sodinokibi Overview

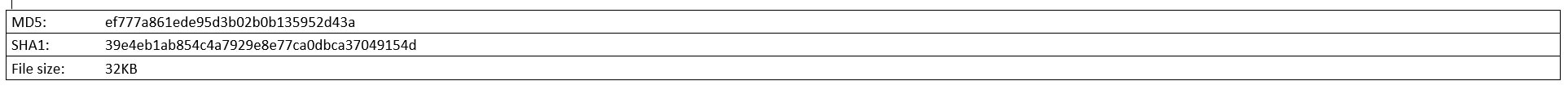

For this article we researched the sample with the following hash (packed):

The main goal of this malware, as other ransomware families, is to encrypt your files and then request a payment in return for a decryption tool from the authors or affiliates to decrypt them.

The malware sample we researched is a 32-bit binary, with an icon in the packed file and without one in the unpacked file. The packer is programmed in Visual C++ and the malware itself is written in pure assembly.

Technical Details

The goal of the packer is to decrypt the true malware part and use a RunPE technique to run it from memory. To obtain the malware from memory, after the decryption is finished and is loaded into the memory, we dumped it to obtain an unpacked version.

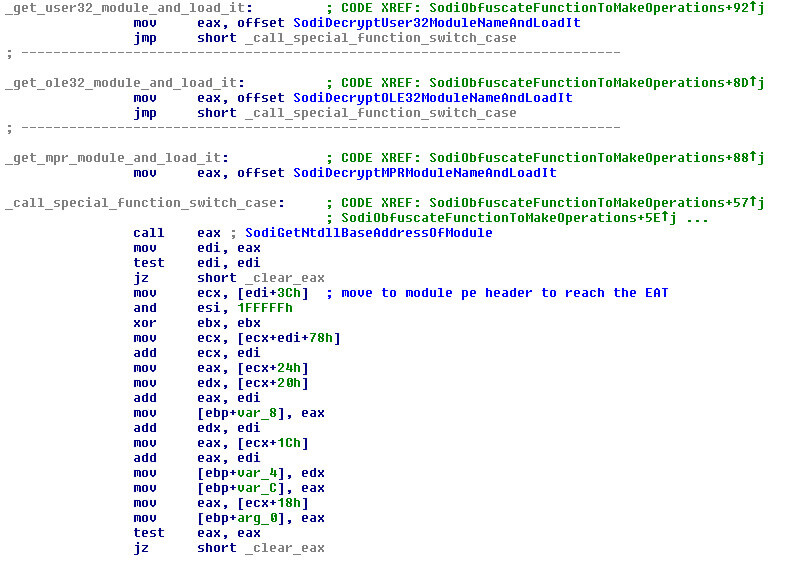

The first action of the malware is to get all functions needed in runtime and make a dynamic IAT to try obfuscating the Windows call in a static analysis.

FIGURE 2. THE MALWARE GETS ALL FUNCTIONS NEEDED IN RUNTIME

FIGURE 2. THE MALWARE GETS ALL FUNCTIONS NEEDED IN RUNTIME

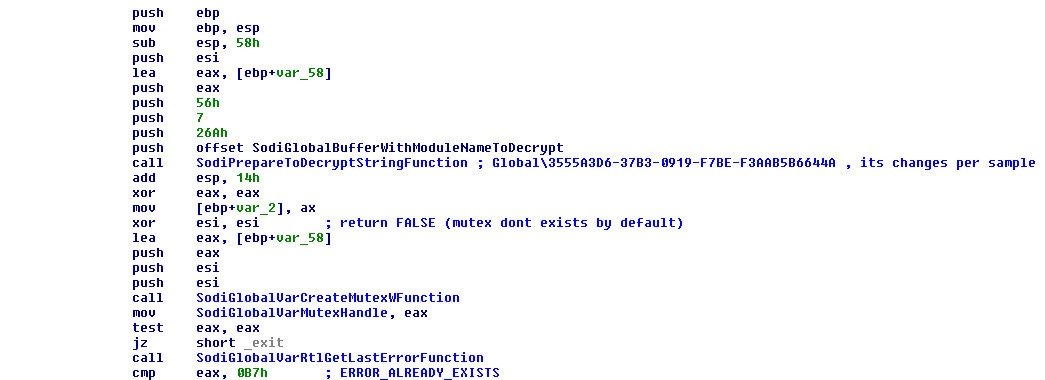

The next action of the malware is trying to create a mutex with a hardcoded name. It is important to know that the malware has 95% of the strings encrypted inside. Consider that each sample of the malware has different strings in a lot of places; values as keys or seeds change all the time to avoid what we, as an industry do, namely making vaccines or creating one decryptor without taking the values from the specific malware sample to decrypt the strings.

FIGURE 3. CREATION OF A MUTEX AND CHECK TO SEE IF IT ALREADY EXISTS

FIGURE 3. CREATION OF A MUTEX AND CHECK TO SEE IF IT ALREADY EXISTS

If the mutex exists, the malware finishes with a call to “ExitProcess.” This is done to avoid re-launching of the ransomware.

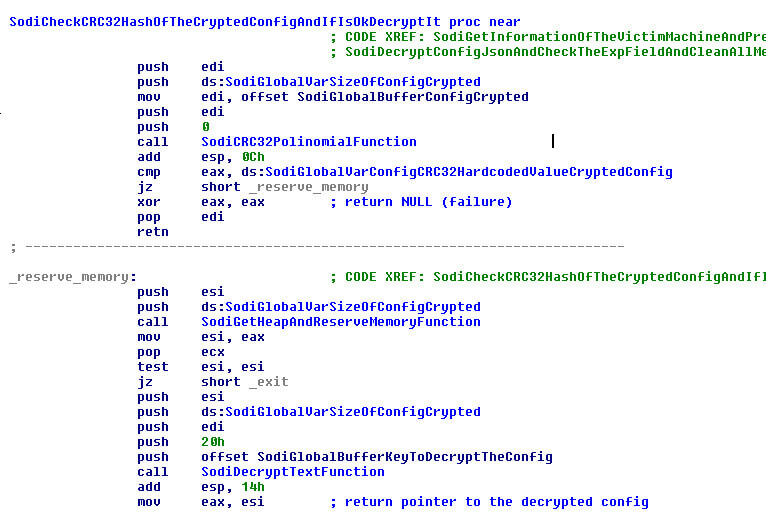

After this mutex operation the malware calculates a CRC32 hash of a part of its data using a special seed that changes per sample too. This CRC32 operation is based on a CRC32 polynomial operation instead of tables to make it faster and the code-size smaller.

The next step is decrypting this block of data if the CRC32 check passes with success. If the check is a failure, the malware will ignore this flow of code and try to use an exploit as will be explained later in the report.

FIGURE 4. CALCULATION OF THE CRC32 HASH OF THE CRYPTED CONFIG AND DECRYPTION IF IT PASSES THE CHECK

FIGURE 4. CALCULATION OF THE CRC32 HASH OF THE CRYPTED CONFIG AND DECRYPTION IF IT PASSES THE CHECK

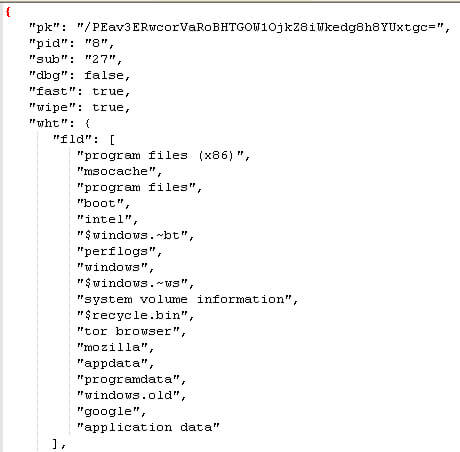

In the case that the malware passes the CRC32 check and decrypts correctly with a key that changes per sample, the block of data will get a JSON file in memory that will be parsed. This config file has fields to prepare the keys later to encrypt the victim key and more information that will alter the behavior of the malware.

The CRC32 check avoids the possibility that somebody can change the crypted data with another config and does not update the CRC32 value in the malware.

After decryption of the JSON file, the malware will parse it with a code of a full JSON parser and extract all fields and save the values of these fields in the memory.

FIGURE 5. PARTIAL EXAMPLE OF THE CONFIG DECRYPTED AND CLEANED

FIGURE 5. PARTIAL EXAMPLE OF THE CONFIG DECRYPTED AND CLEANED

Let us explain all the fields in the config and their meanings:

- pk -> This value encoded in base64 is important later for the crypto process; it is the public key of the attacker.

- pid -> The affiliate number that belongs to the sample.

- sub -> The subaccount or campaign id for this sample that the affiliate uses to keep track of its payments.

- dbg -> Debug option. In the final version this is used to check if some things have been done or not; it is a development option that can be true or false. In the samples in the wild it is in the false state. If it is set, the keyboard check later will not happen. It is useful for the malware developers to prove the malware works correctly in the critical part without detecting his/her own machines based on the language.

- fast -> If this option is enabled, and by default a lot of samples have it enabled, the malware will crypt the first 1 megabyte of each target file, or all files if it is smaller than this size. In the case that this field is false, it will crypt all files.

- wipe -> If this option is ‘true’, the malware will destroy the target files in the folders that are described in the json field “wfld”. This destruction happens in all folders that have the name or names that appear in this field of the config in logic units and network shares. The overwriting of the files can be with trash data or null data, depending of the sample.

- wht -> This field has some subfields: fld -> Folders that should not be crypted; they are whitelisted to avoid destroying critical files in the system and programs. fls -> List of whitelists of files per name; these files will never be crypted and this is useful to avoid destroying critical files in the system. ext -> List of the target extensions to avoid encrypting based on extension.

- wfld -> A list of folders where the files will be destroyed if the wipe option is enabled.

- prc -> List of processes to kill for unlocking files that are locked by this/these program/s, for example, “mysql.exe”.

- dmn -> List of domains that will be used for the malware if the net option is enabled; this list can change per sample, to send information of the victim.

- net -> This value can be false or true. By default, it is usually true, meaning that the malware will send information about the victim if they have Internet access to the domain list in the field “dmn” in the config.

- nbody -> A big string encoded in base64 that is the template for the ransom note that will appear in each folder where the malware can create it.

- nname -> The string of the name of the malware for the ransom note file. It is a template that will have a part that will be random in the execution.

- exp -> This field is very important in the config. By default it will usually be ‘false’, but if it is ‘true’, or if the check of the hash of the config fails, it will use the exploit CVE-2018-8453. The malware has this value as false by default because this exploit does not always work and can cause a Blue Screen of Death that avoids the malware’s goal to encrypt the files and request the ransom. If the exploit works, it will elevate the process to SYSTEM user.

- img -> A string encoded in base64. It is the template for the image that the malware will create in runtime to change the wallpaper of the desktop with this text.

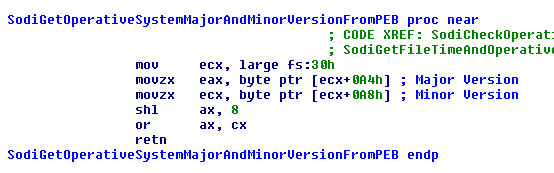

After decrypting the malware config, it parses it and the malware will check the “exp” field and if the value is ‘true’, it will detect the type of the operative system using the PEB fields that reports the major and minor version of the OS.

FIGURE 6. CHECK OF THE VERSION OF THE OPERATIVE SYSTEM

FIGURE 6. CHECK OF THE VERSION OF THE OPERATIVE SYSTEM

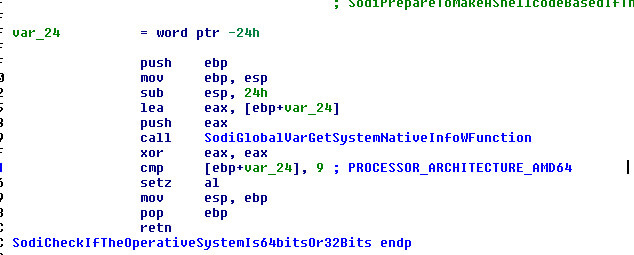

Usually only one OS can be found but that is enough for the malware. The malware will check the file-time to verify if the date was before or after a patch was installed to fix the exploit. If the file time is before the file time of the patch, it will check if the OS is 64-bit or 32-bit using the function “GetSystemNativeInfoW”. When the OS system is 32-bit, it will use a shellcode embedded in the malware that is the exploit and, in the case of a 64-bit OS, it will use another shellcode that can use a “Heaven´s Gate” to execute code of 64 bits in a process of 32 bits.

FIGURE 7. CHECK IF OS IS 32- OR 64-BIT

FIGURE 7. CHECK IF OS IS 32- OR 64-BIT

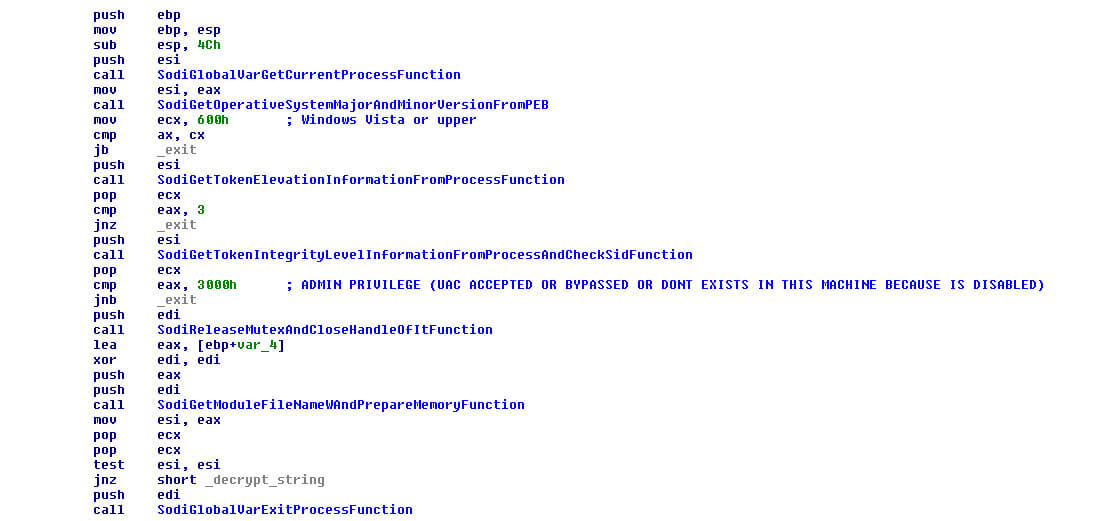

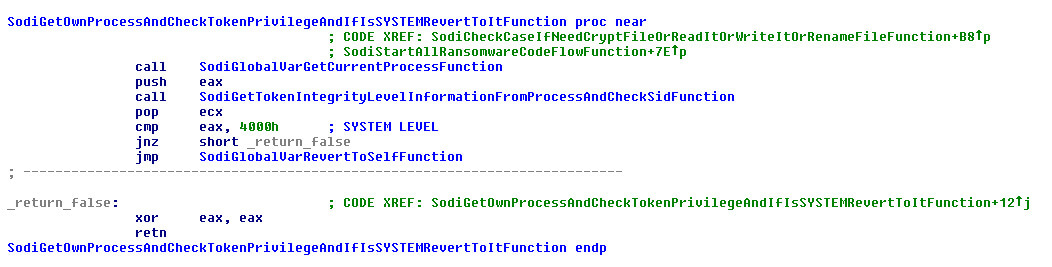

In the case that the field was false, or the exploit is patched, the malware will check the OS version again using the PEB. If the OS is Windows Vista, at least it will get from the own process token the level of execution privilege. When the discovered privilege level is less than 0x3000 (that means that the process is running as a real administrator in the system or SYSTEM), it will relaunch the process using the ‘runas’ command to elevate to 0x3000 process from 0x2000 or 0x1000 level of execution. After relaunching itself with the ‘runas’ command the malware instance will finish.

FIGURE 8. CHECK IF OS IS WINDOWS VISTA MINIMAL AND CHECK OF EXECUTION LEVEL

FIGURE 8. CHECK IF OS IS WINDOWS VISTA MINIMAL AND CHECK OF EXECUTION LEVEL

The malware’s next action is to check if the execute privilege is SYSTEM. When the execute privilege is SYSTEM, the malware will get the process “Explorer.exe”, get the token of the user that launched the process and impersonate it. It is a downgrade from SYSTEM to another user with less privileges to avoid affecting the desktop of the SYSTEM user later.

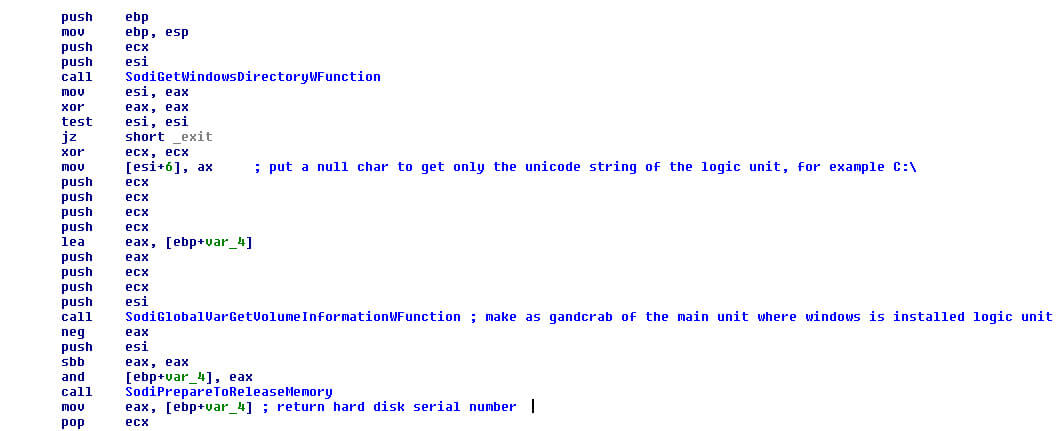

After this it will parse again the config and get information of the victim’s machine This information is the user of the machine, the name of the machine, etc. The malware prepares a victim id to know who is affected based in two 32-bit values concat in one string in hexadecimal.

The first part of these two values is the serial number of the hard disk of the Windows main logic unit, and the second one is the CRC32 hash value that comes from the CRC32 hash of the serial number of the Windows logic main unit with a seed hardcoded that change per sample.

FIGURE 9. GET DISK SERIAL NUMBER TO MAKE CRC32 HASH

FIGURE 9. GET DISK SERIAL NUMBER TO MAKE CRC32 HASH

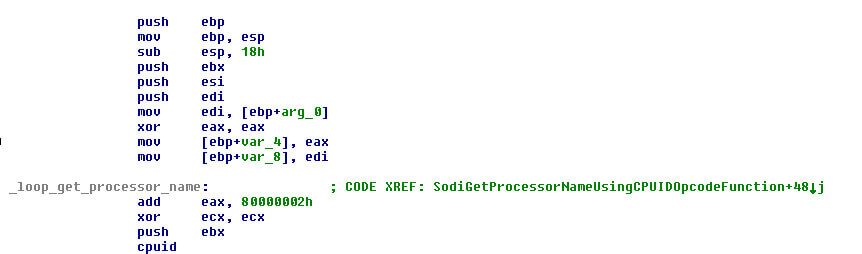

After this, the result is used as a seed to make the CRC32 hash of the name of the processor of the machine. But this name of the processor is not extracted using the Windows API as GandCrab does; in this case the malware authors use the opcode CPUID to try to make it more obfuscated.

FIGURE 10. GET THE PROCESSOR NAME USING CPUID OPCODE

FIGURE 10. GET THE PROCESSOR NAME USING CPUID OPCODE

Finally, it converts these values in a string in a hexadecimal representation and saves it.

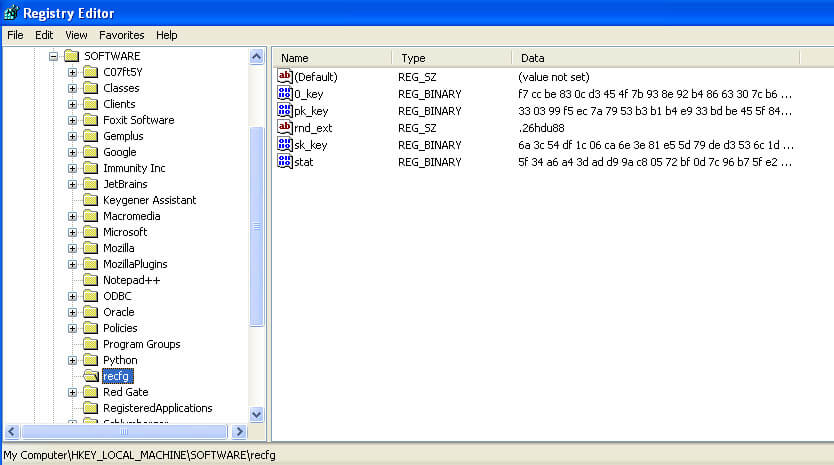

Later, during the execution, the malware will write in the Windows registry the next entries in the subkey “SOFTWARE\recfg” (this subkey can change in some samples but usually does not).

The key entries are:

- 0_key -> Type binary; this is the master key (includes the victim’s generated random key to crypt later together with the key of the malware authors).

- sk_key -> As 0_key entry, it is the victim’s private key crypted but with the affiliate public key hardcoded in the sample. It is the key used in the decryptor by the affiliate, but it means that the malware authors can always decrypt any file crypted with any sample as a secondary resource to decrypt the files.

- pk_key -> Victim public key derivate from the private key.

- subkey -> Affiliate public key to use.

- stat -> The information gathered from the victim machine and used to put in the ransom note crypted and in the POST send to domains.

- rnd_ext -> The random extension for the encrypted files (can be from 5 to 10 alphanumeric characters).

The malware tries to write the subkey and the entries in the HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE hive at first glance and, if it fails, it will write them in the HKEY_CURRENT_USER hive.

FIGURE 11. EXAMPLE OF REGISTRY ENTRIES AND SUBKEY IN THE HKLM HIVE

FIGURE 11. EXAMPLE OF REGISTRY ENTRIES AND SUBKEY IN THE HKLM HIVE

The information that the malware gets from the victim machine can be the user name, the machine name, the domain where the machine belongs or, if not, the workgroup, the product name (operating system name), etc.

After this step is completed, the malware will check the “dbg” option gathered from the config and, if that value is ‘true’, it will avoid checking the language of the machine but if the value is ‘false’ ( by default), it will check the machine language and compare it with a list of hardcoded values.

FIGURE 12. GET THE KEYBOARD LANGUAGE OF THE SYSTEM

FIGURE 12. GET THE KEYBOARD LANGUAGE OF THE SYSTEM

The malware checks against the next list of blacklisted languages (they can change per sample in some cases):

- **0x818 –**Romanian (Moldova)

- **0x419 –**Russian

- **0x819 –**Russian (Moldova)

- **0x422 –**Ukrainian

- **0x423 –**Belarusian

- **0x425 –**Estonian

- **0x426 –**Latvian

- **0x427 –**Lithuanian

- **0x428 –**Tajik

- **0x429 –**Persian

- **0x42B –**Armenian

- **0x42C –**Azeri

- **0x437 –**Georgian

- **0x43F –**Kazakh

- **0x440 –**Kyrgyz

- **0x442 –**Turkmen

- **0x443 –**Uzbek

- **0x444 –**Tatar

- **0x45A –**Syrian

- **0x2801 –**Arabic (Syria)

We observed that Sodinokibi, like GandCrab and Anatova, are blacklisting the regular Syrian language and the Syrian language in Arabic too. If the system contains one of these languages, it will exit without performing any action. If a different language is detected, it will continue in the normal flow.

This is interesting and may hint to an affiliate being involved who has mastery of either one of the languages. This insight became especially interesting later in our investigation.

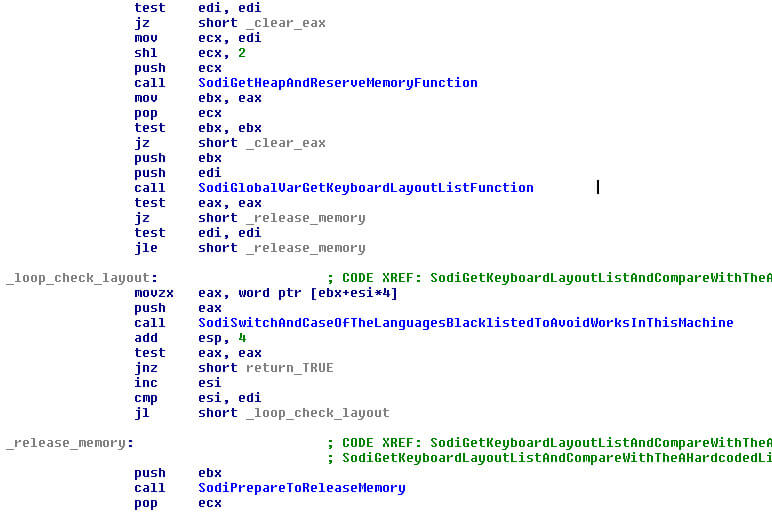

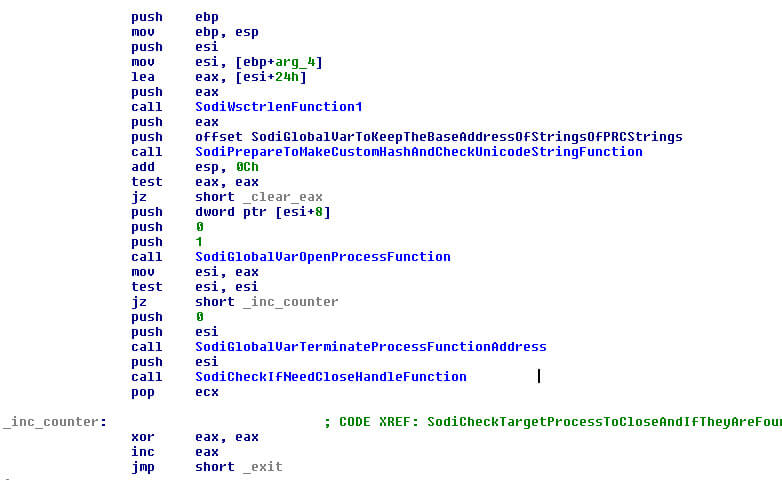

If the malware continues, it will search all processes in the list in the field “prc” in the config and terminate them in a loop to unlock the files locked for this/these process/es.

FIGURE 13. SEARCH FOR TARGET PROCESSES AND TERMINATE THEM

FIGURE 13. SEARCH FOR TARGET PROCESSES AND TERMINATE THEM

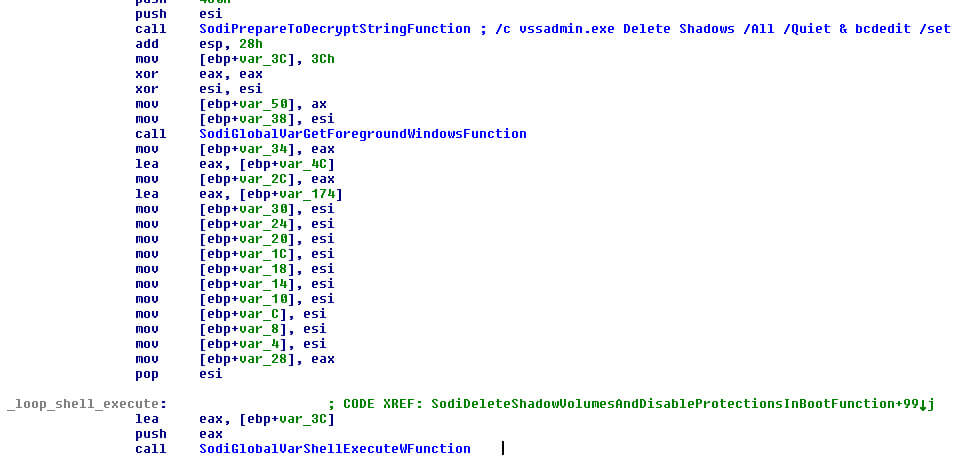

After this it will destroy all shadow volumes of the victim machine and disable the protection of the recovery boot with this command:

- exe /c vssadmin.exe Delete Shadows /All /Quiet & bcdedit /set {default} recoveryenabled No & bcdedit /set {default} bootstatuspolicy ignoreallfailures

It is executed with the Windows function “ShellExecuteW”.

FIGURE 14. LAUNCH COMMAND TO DESTROY SHADOW VOLUMES AND DESTROY SECURITY IN THE BOOT

FIGURE 14. LAUNCH COMMAND TO DESTROY SHADOW VOLUMES AND DESTROY SECURITY IN THE BOOT

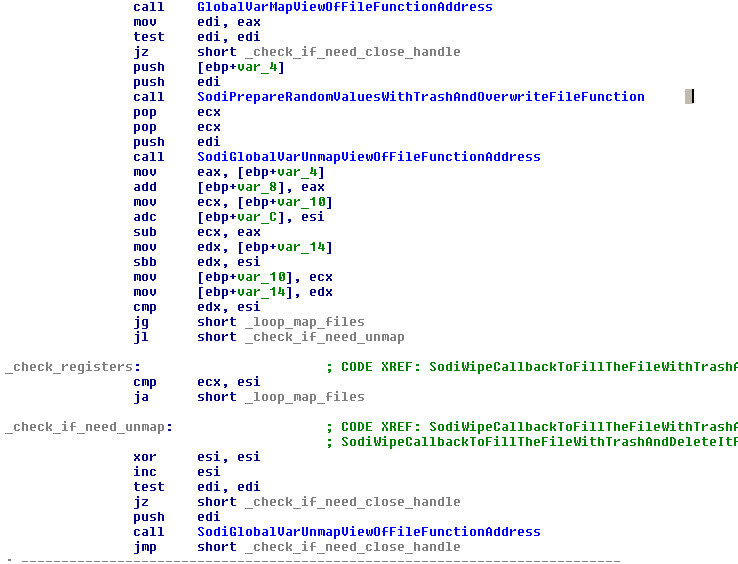

Next it will check the field of the config “wipe” and if it is true will destroy and delete all files with random trash or with NULL values. If the malware destroys the files , it will start enumerating all logic units and finally the network shares in the folders with the name that appear in the config field “wfld”.

FIGURE 15. WIPE FILES IN THE TARGET FOLDERS

FIGURE 15. WIPE FILES IN THE TARGET FOLDERS

In the case where an affiliate creates a sample that has defined a lot of folders in this field, the ransomware can be a solid wiper of the full machine.

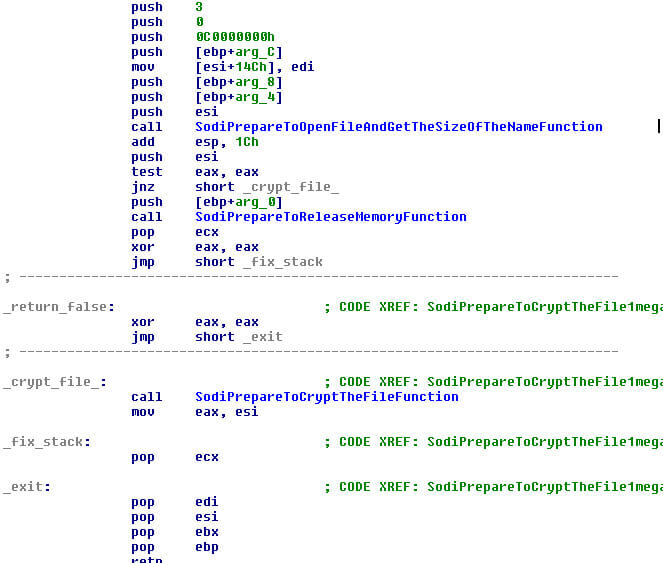

The next action of the malware is its main function, encrypting the files in all logic units and network shares, avoiding the white listed folders and names of files and extensions, and dropping the ransom note prepared from the template in each folder.

FIGURE 16. CRYPT FILES IN THE LOGIC UNITS AND NETWORK SHARES

FIGURE 16. CRYPT FILES IN THE LOGIC UNITS AND NETWORK SHARES

After finishing this step, it will create the image of the desktop in runtime with the text that comes in the config file prepared with the random extension that affect the machine.

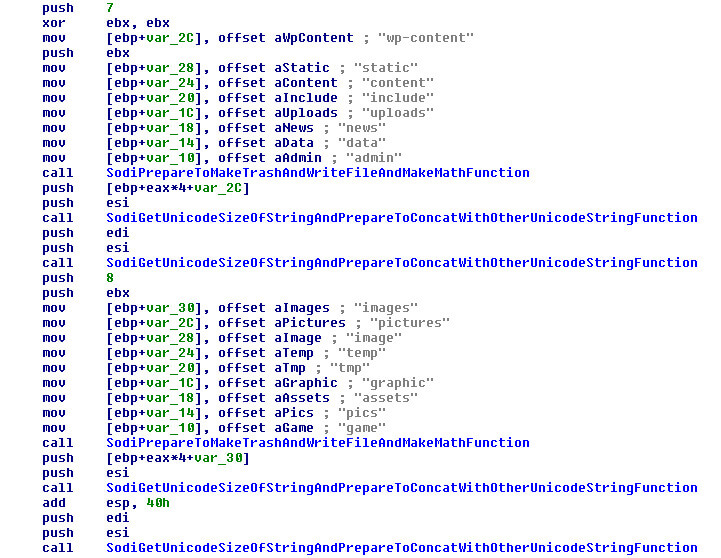

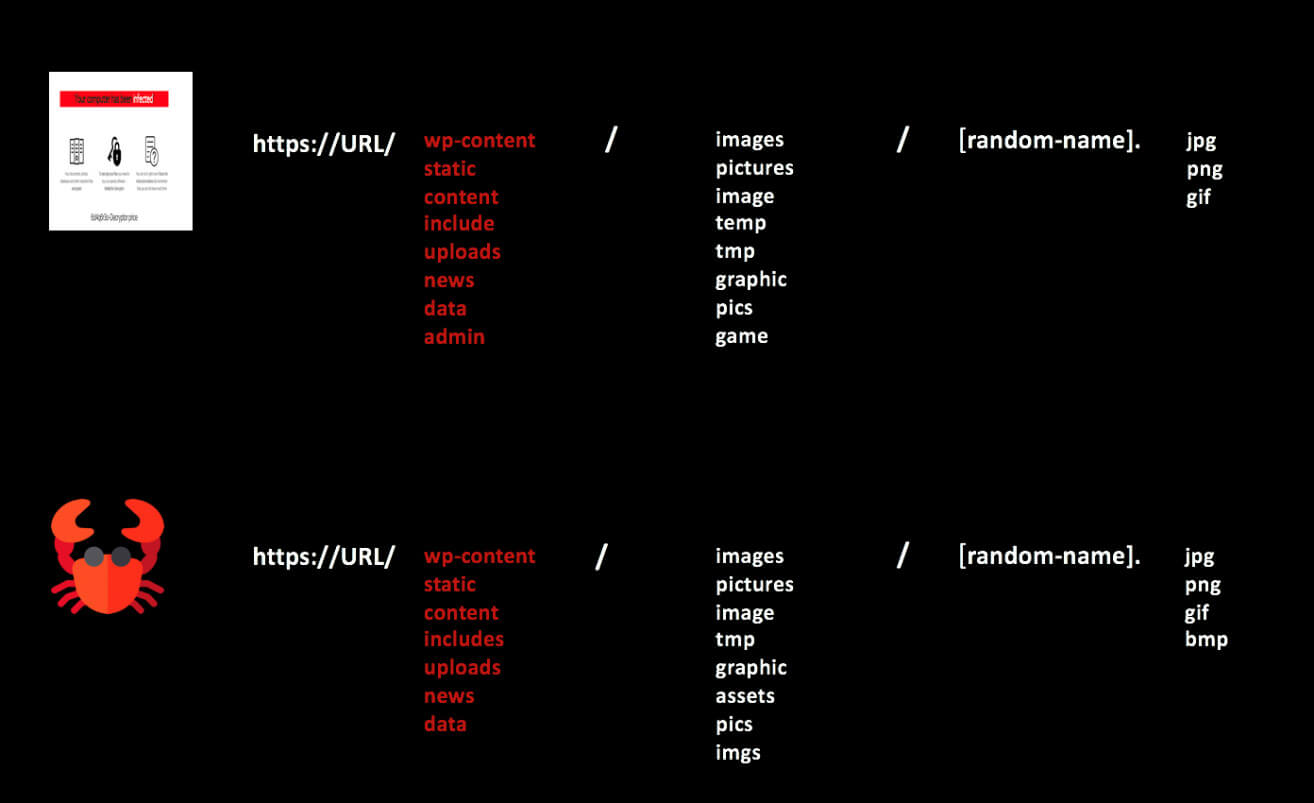

The next step is checking the field “net” from the config, and, if true, will start sending a POST message to the list of domains in the config file in the field “dmn”.

FIGURE 17. PREPARE THE FINAL URL RANDOMLY PER DOMAIN TO MAKE THE POST COMMAND

FIGURE 17. PREPARE THE FINAL URL RANDOMLY PER DOMAIN TO MAKE THE POST COMMAND

This part of the code has similarities to the code of GandCrab, which we will highlight later in this article.

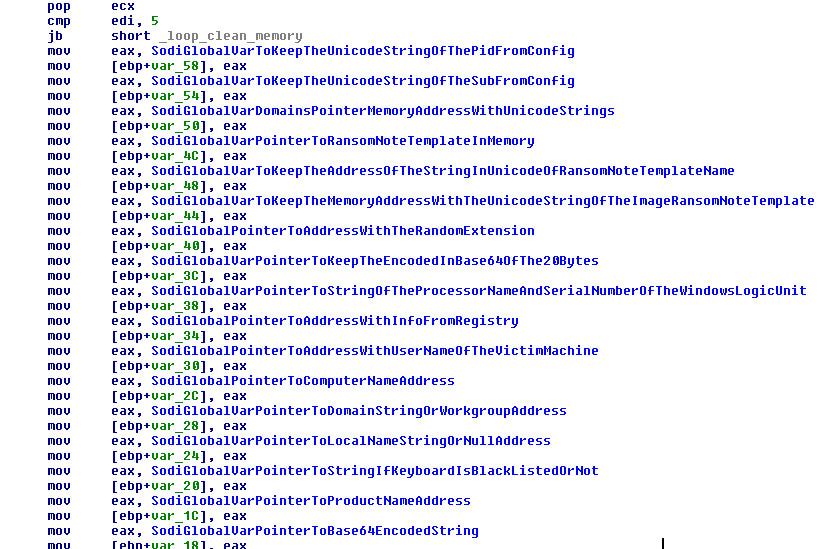

After this step the malware cleans its own memory in vars and strings but does not remove the malware code, but it does remove the critical contents to avoid dumps or forensics tools that can gather some information from the RAM.

FIGURE 18. CLEAN MEMORY OF VARS

FIGURE 18. CLEAN MEMORY OF VARS

If the malware was running as SYSTEM after the exploit, it will revert its rights and finally finish its execution.

FIGURE 19. REVERT THE SYSTEM PRIVILEGE EXECUTION LEVEL

FIGURE 19. REVERT THE SYSTEM PRIVILEGE EXECUTION LEVEL

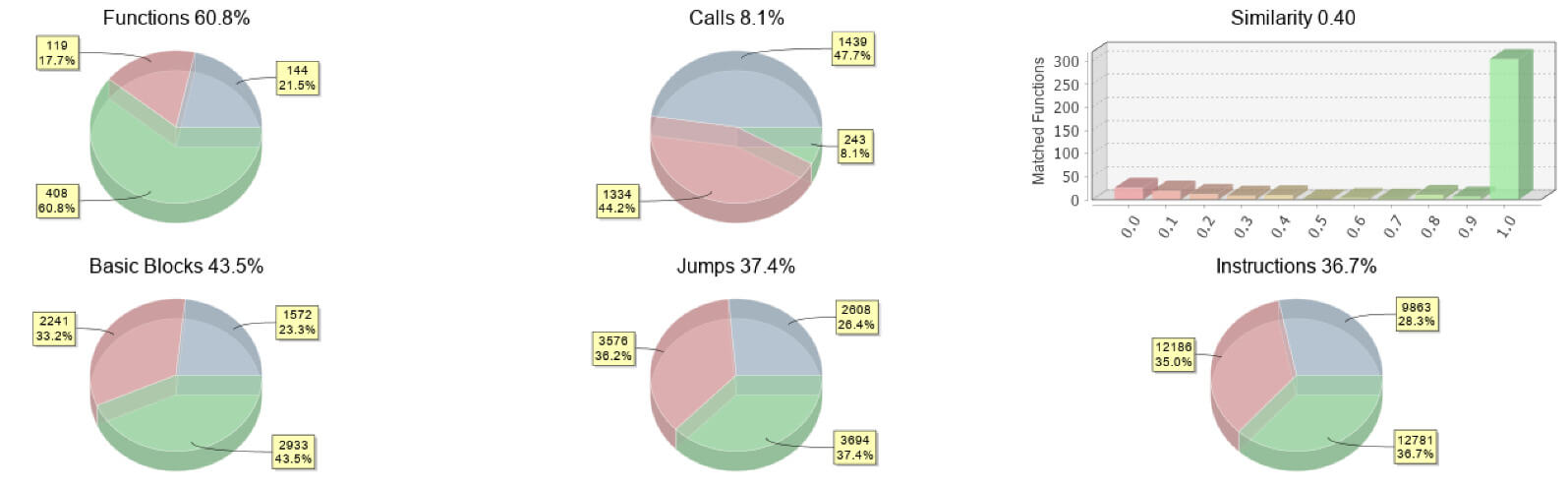

Code Comparison with GandCrab

Using the unpacked Sodinokibi sample and a v5.03 version of GandCrab, we started to use IDA and BinDiff to observe any similarities. Based on the Call-Graph it seems that there is an overall 40 percent code overlap between the two:

FIGURE 20. CALL-GRAPH COMPARISON

FIGURE 20. CALL-GRAPH COMPARISON

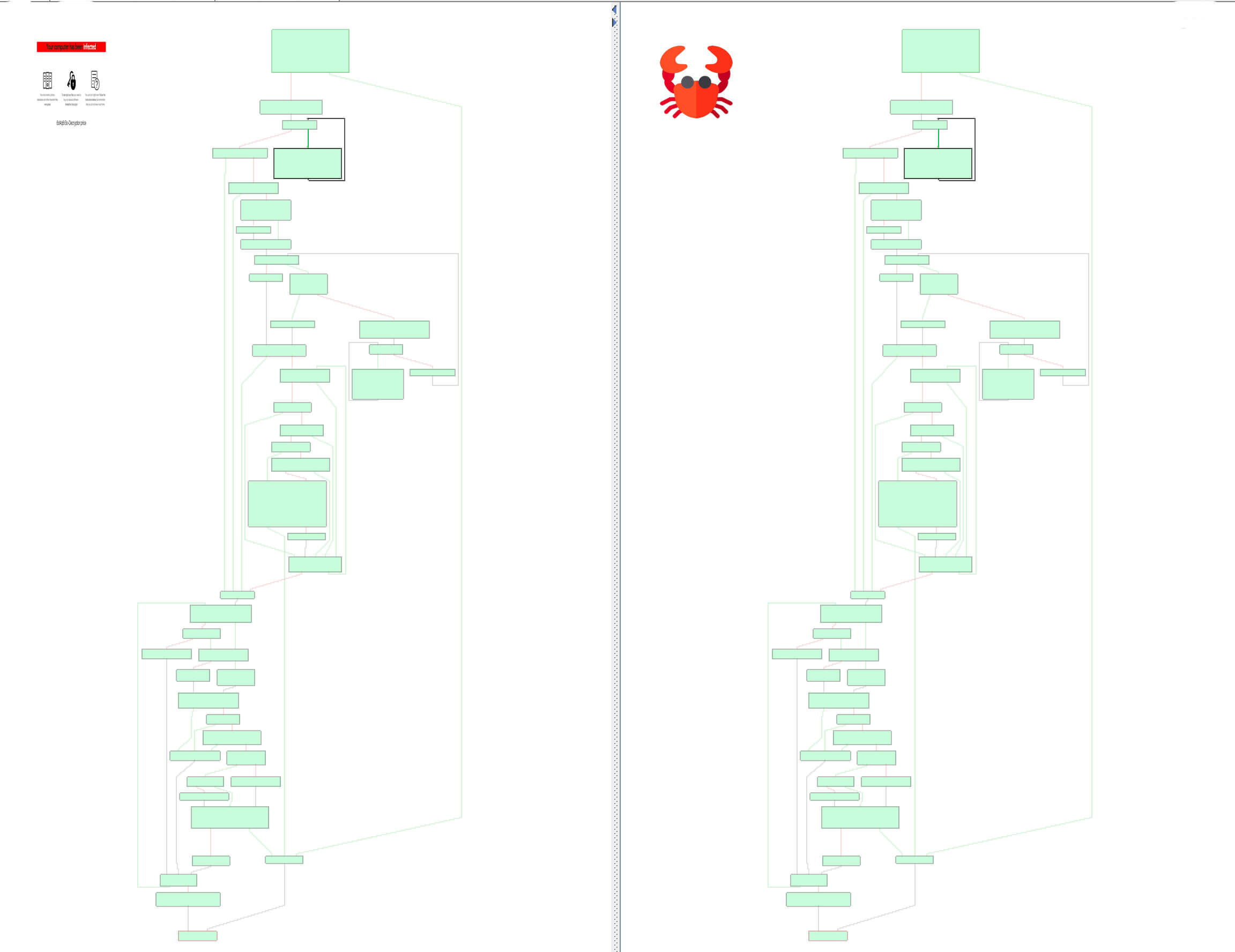

The most overlap seems to be in the functions of both families. Although values change, going through the code reveals similar patterns and flows:

Although here and there are some differences, the structure is similar:

We already mentioned that the code part responsible for the random URL generation has similarities with regards to how it is generated in the GandCrab malware. Sodinokibi is using one function to execute this part where GandCrab is using three functions to generate the random URL. Where we do see some similar structure is in the parts for the to-be-generated URL in both malware codes. We created a visual to explain the comparison better:

FIGURE 21. URL GENERATION COMPARISON

FIGURE 21. URL GENERATION COMPARISON

We observe how even though the way both ransomware families generate the URL might differ, the URL directories and file extensions used have a similarity that seems to be more than coincidence. This observation was also discovered by Tesorion in one of its blogs.

Overall, looking at the structure and coincidences, either the developers of the GandCrab code used it as a base for creating a new family or, another hypothesis, is that people got hold of the leaked GandCrab source code and started the new RaaS Sodinokibi.

Conclusion

Sodinokibi is a serious new ransomware threat that is hitting many victims all over the world.

We executed an in-depth analysis comparing GandCrab and Sodinokibi and discovered a lot of similarities, indicating the developer of Sodinokibi had access to GandCrab source-code and improvements. The Sodinokibi campaigns are ongoing and differ in skills and tools due to the different affiliates operating these campaigns, which begs more questions to be answered. How do they operate? And is the affiliate model working? McAfee ATR has the answers in episode 2, “The All Stars.”

Coverage

McAfee is detecting this family by the following signatures:

- “Ransom-Sodinokibi”

- “Ransom-REvil!”.

MITRE ATT&CK Techniques

The malware sample uses the following MITRE ATT&CK™ techniques:

- File and Directory Discovery

- File Deletion

- Modify Registry

- Query Registry

- Registry modification

- Query information of the user

- Crypt Files

- Destroy Files

- Make C2 connections to send information of the victim

- Modify system configuration

- Elevate privileges

YARA Rule

rule Sodinokobi

{

/*

This rule detects Sodinokobi Ransomware in memory in old samples and perhaps future.

*/

meta:

author = “McAfee ATR team”

version = “1.0”

description = “This rule detect Sodinokobi Ransomware in memory in old samples and perhaps future.”

strings:

$a = { 40 0F B6 C8 89 4D FC 8A 94 0D FC FE FF FF 0F B6 C2 03 C6 0F B6 F0 8A 84 35 FC FE FF FF 88 84 0D FC FE FF FF 88 94 35 FC FE FF FF 0F B6 8C 0D FC FE FF FF }

$b = { 0F B6 C2 03 C8 8B 45 14 0F B6 C9 8A 8C 0D FC FE FF FF 32 0C 07 88 08 40 89 45 14 8B 45 FC 83 EB 01 75 AA }

condition:

all of them

}