Heatmiser WiFi thermostat vulnerabilities

Update – if your heating is misbehaving you need to disable port forwarding to port 80 and port 8068. This should be simply following the reverse of whatever you did to set port forwarding up. Alternatively, you could disable WiFi entirely by putting invalid SSID and password in – I believe the thermostats should continue to work.

Contact [email protected] for an official response.

A while back, I came across a page listing some vulnerabilities on Heatmiser’s Netmonitor product. The Netmonitor is old and discontinued though, so maybe some lessons have been learnt.

I thought I’d take a quick look at the rest of their product line. They have a series of products, generally called WiFi thermostats that connect directly to your router using 802.11b. The products aren’t listed on their site (possibly removed after reporting this), but this Amazon listing gives you an idea.

This is a WiFi thermostat running version v1.2 of the firmware. There are newer versions of the firmware – up to v1.7 as far as I can see.

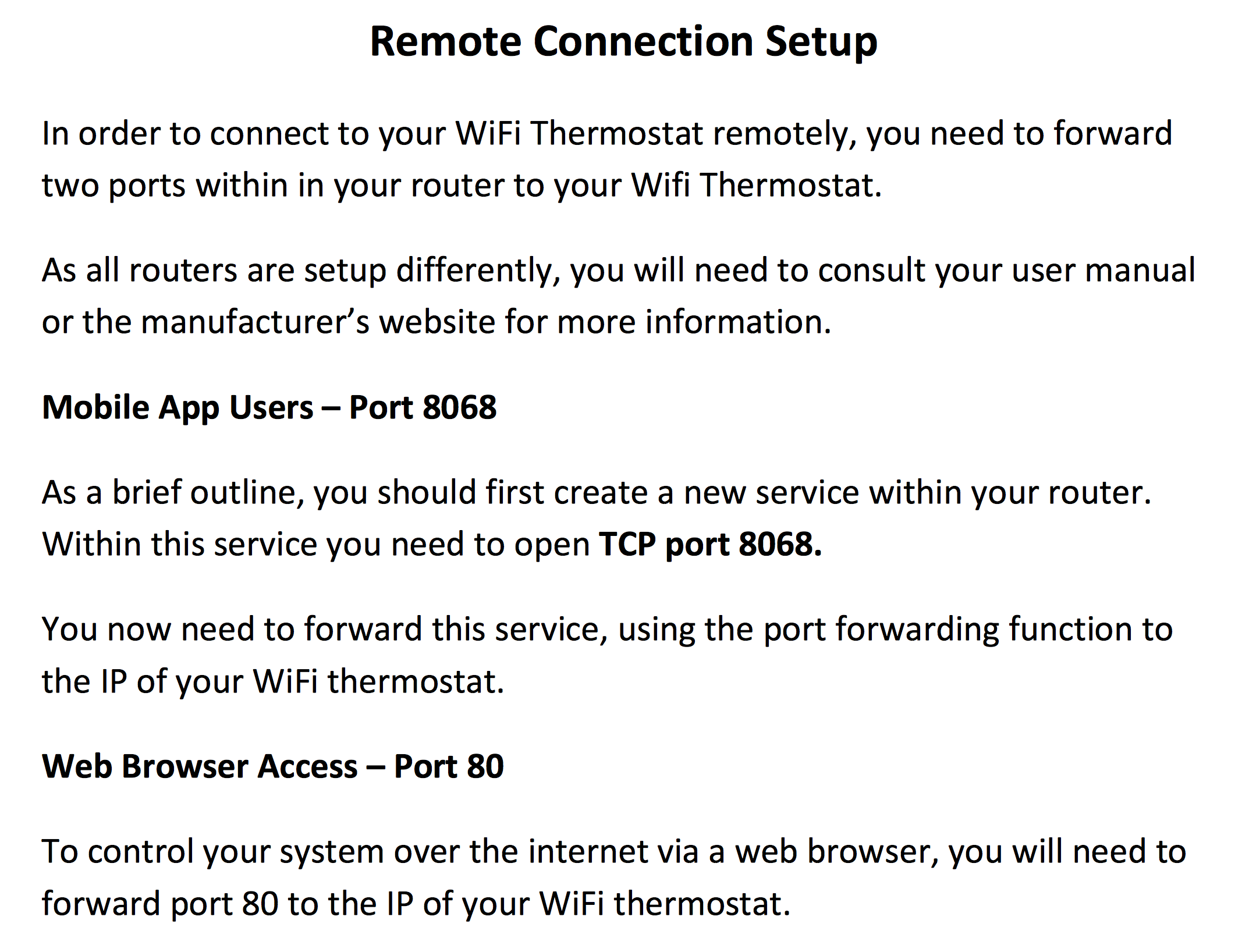

A quick look at the manuals shows that Heatmiser recommend two ports are forwarded to the thermostat from the router- port 80 for web control and port 8068 for app control.

Port forwarding to a small embedded device is an easy way to get access to the device remotely, but it also puts you at risk. That device is now entirely open to the wider Internet on port 80 and 8068.

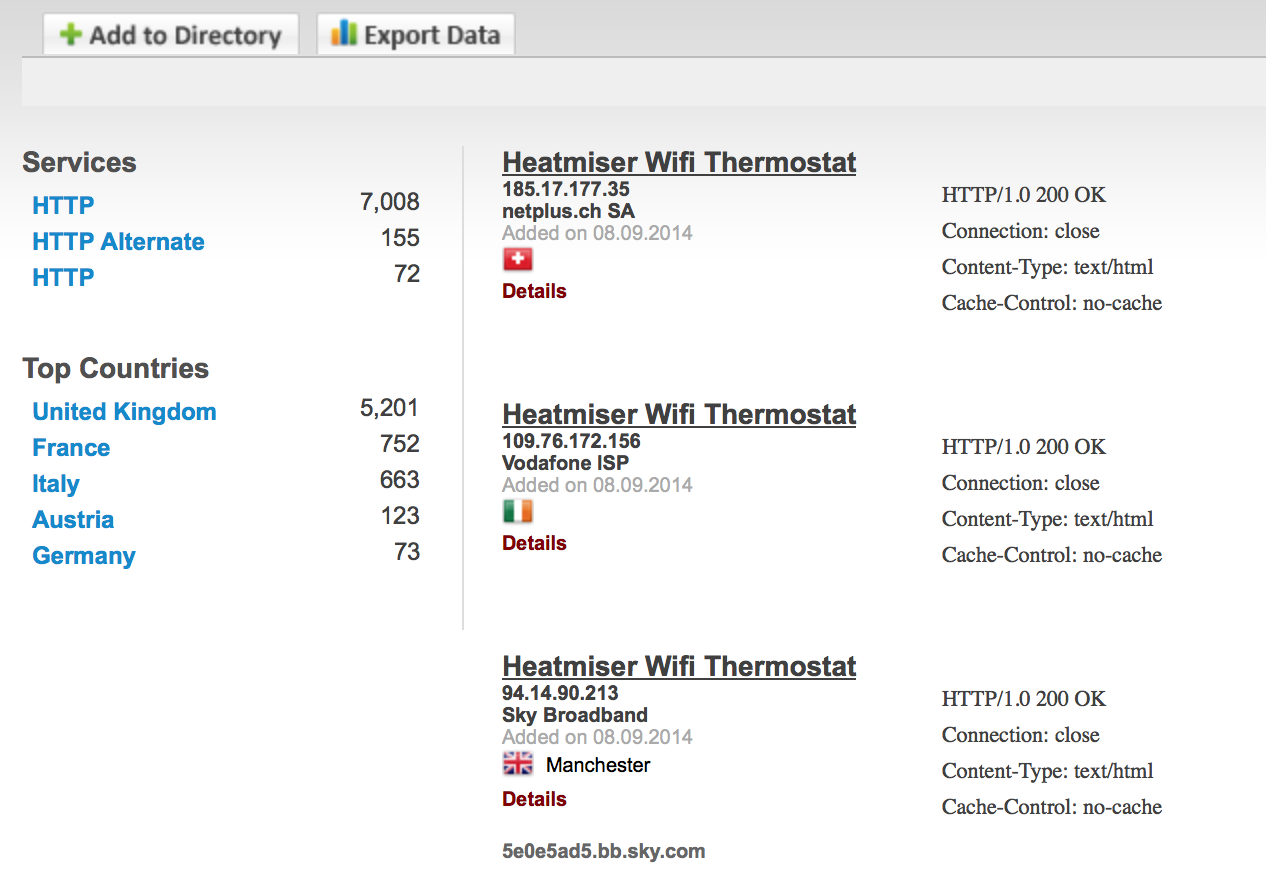

Also of note – a quick google search for port 8068 shows that the Heatmiser is the most common reason to have port 8068 open. This makes finding Heatmiser thermostats much easier. Scanning for them on port 80 is slow. Port 80 could be any web page, so you need to check for port 80 being open, connect, perform a HTTP request, and then check the content of a web page (e.g. does the title contain “Heatmiser”).

Scanning for Heatmiser thermostats on port 8068 really just requires a quick check for port 8068 being open – we can be fairly confident that anything with this port open is one of their devices. We can then make detailed check on port 80.

nmap -p 8068 -Pn -T 5 --open 78.12.1-254.1-254

nmap can easily do this scan. If you want to scan large blocks of addresses though, masscan is much faster.

However, other people have already done the hard work for us – Shodan search engine scans all IPs, connects to port 80 and records the results. We just need a search term. This is simple – the title of the page is always “Heatmiser Wifi Thermostat”.

Plugging this into Shodan we get over 7000 results. That’s quite a lot. (note, you might need to register to use filters like this).

Issue 1 – default web credentials and PIN

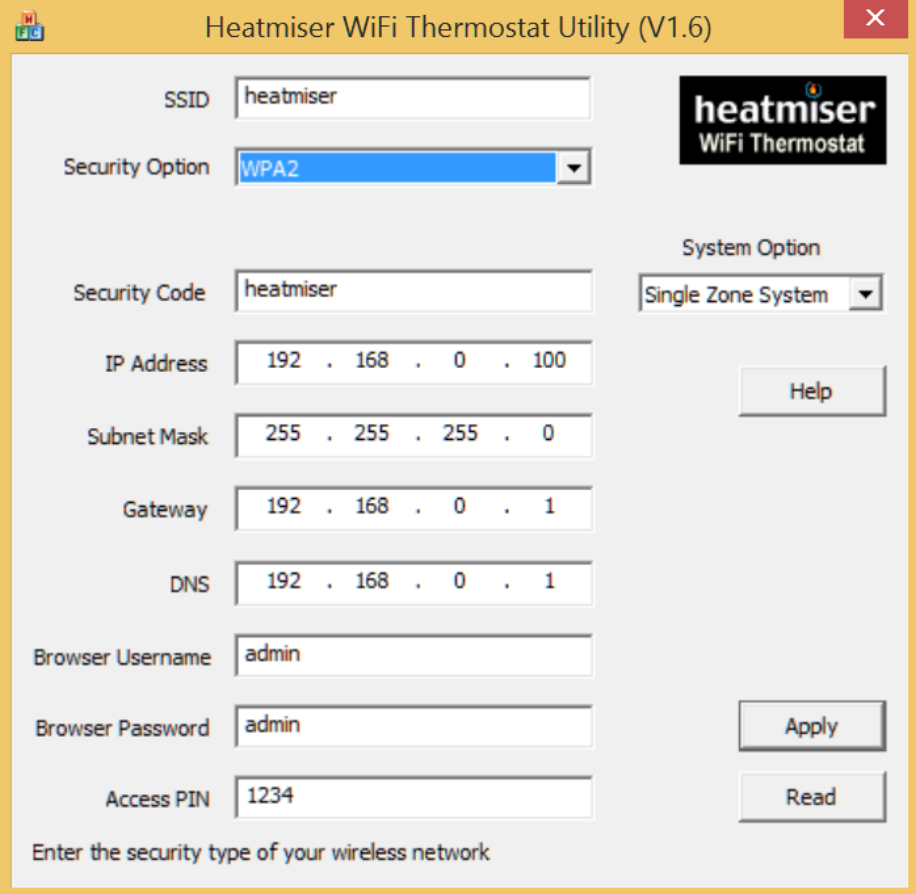

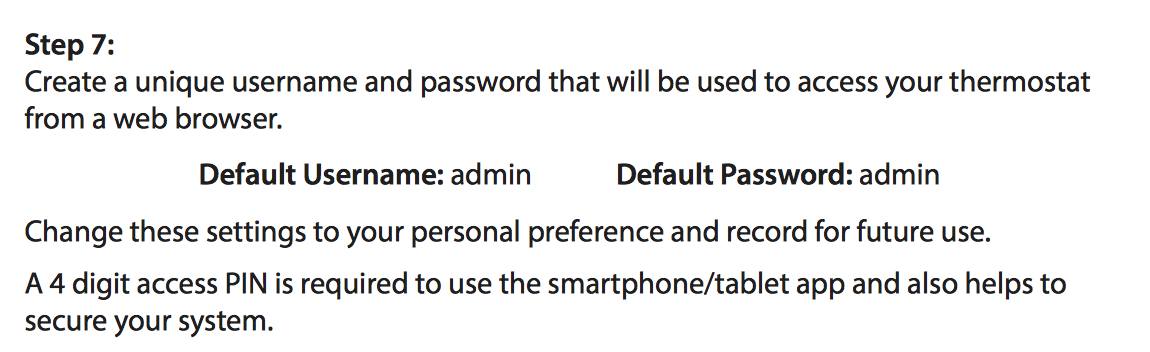

To configure the thermostat, you connect with USB and use a Windows utility. In here you can set the username/password for the web interface and the PIN for port 8068 app access.

The application defaults to admin/admin and PIN 1234.

Even the manual suggests the default username and password.

It’s essential that an internet connected device enforces a custom password of decent strength. This isn’t even suggested or prompted for, never mind enforced.

Heatmiser’s response is that the password should be changed. My response is that their software shouldn’t allow defaults.

Issue 2 – wifi credentials and password can be seen in the plain

When logged into one of the devices, the username, password, WiFi SSID and WiFi password are all filled into the form and can be viewed easily by examine the source of the webpage.

There is really no excuse for this – it’s lazy.

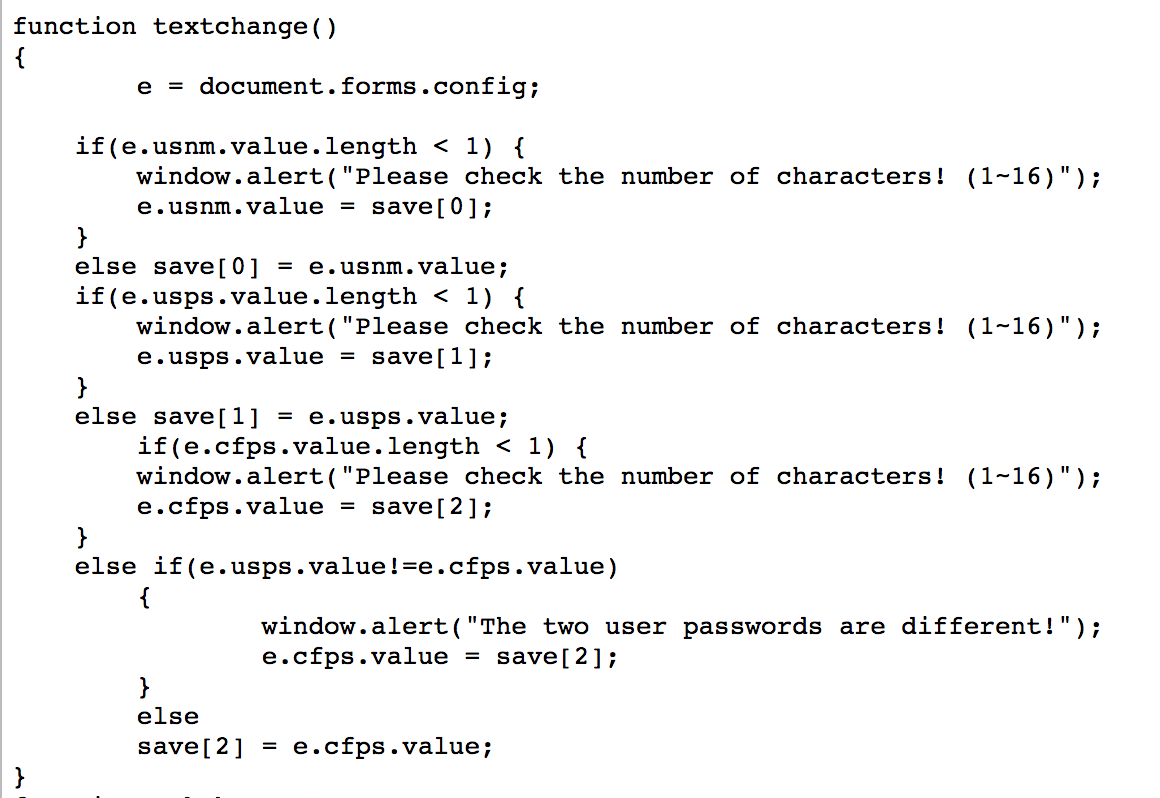

Issue 3 – in-browser user input validation/sanitising

Viewing the source of several pages, it can be seen that the user input input is being validated and sanitised by Javascript.

Why is this an issue? Because often this means no checks are done by the device itself after input is submitted. All you need to do to pass invalid or dangerous data is not use a web-browser to send requests. Use a custom client that performs the same action without the validation.

This opens up many potential attacks.

This seems quite common with low-end processors connected to the Internet. The browser has a lot more power and is a lot more responsive, so checks in-browser often seem attractive.

Issue 4 – open to CSRF attacks

Once logged into the device with a given client (e.g. Chrome), other clients on the same machine can access the device as if they were logged in.

This enables an attack technique called cross-site request forgery. It means that I can send a user a link containing a malicious request and the device will blindly carry it out. For example, I could send a request to change the password to one of my choosing in an email, and as long as the user has logged into the thermostat recently, that request will be carried out by the device.

Best practice would dictate that only requests from pages generated by the device itself would work.

There are a number of ways to protect against CSRF – it’s actually quite complex to do, but this device has no protection at all.

It gets worse though. It appears the authentication works only by IP address. Once the thermostat sees you have logged in from a given IP address, any requests from that IP address will work.

This is a really bad thing to do.

Most homes and workplaces use something called NAT on their routers. This means that all of your laptops, PCs, phones, consoles and tablets all appear to have the same IP to anyone looking from the outside. If I log in to my thermostat from work, it’s likely that the IP address the thermostat sees is also in use by a number of other people.

This means that if I log in to my thermostat at work, anyone else in my workplace can access my thermostat simply by visiting the page without any need for credentials.

As I said, protecting against CSRF is hard but this is as vulnerable as it gets to CSRF.

Issue 5 – no rate limiting or lockout on the port 8068 PIN

The Android and iPhone apps access the device on port 8068 using a custom protocol. Part of this involves sending the 4 digit PIN number to authenticate the app.

A 4 digit PIN only has 10,000 combinations and no username component. This makes brute forcing a PIN number very easy, so it is vital that there is rate-limiting or a lockout e.g. maximum 3 failed PIN attempts followed by a 10 minute lockout.

There is no rate limiting on the WiFi thermostats. You can try about 2 PINs/second over the Internet i.e. going through all 10,000 PINs takes about 1.5hr.

Now and then requests time-out when attempting PINs rapidly, but I suspect this is just a limitation of a low-power embedded device.

Even a fairly conservative lockout of 10 minutes after 3 wrong attempts would increase this to 23 days.

I have written a proof-of-concept to brute force the PIN but don’t want to release it openly currently.

Issue 6 – no means of updating firmware without a physical programmer and taking the device apart

Fixing issues in embedded, Internet connected devices requires a firmware update.

The WiFi thermostat appears to have no way of doing this remotely or via the web interface. It requires borrowing a programmer from Heatmiser (after paying a deposit), removing the device from the wall and updating it.

This is such a large barrier that very few people are going to do it. This creates an ethos and dynamic where neither the company or the customer is driven to fix or deploy security issues. The source for this little nugget of info started from this page here – where someone describes the process in the comments.

Issue 7 – trivial web authentication bypass

Go to the IP of any Heatmiser thermostat in a browser and you get the login box (often along with an annoying Javascript pop-up telling you the username/password is wrong for no reason).

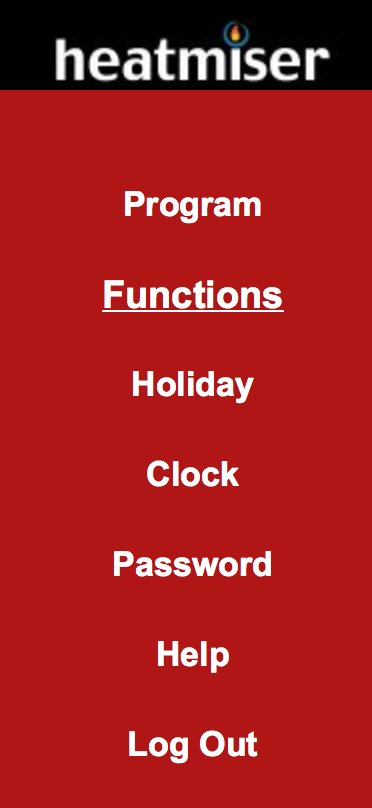

Give it the right password and you end up on a framed window with several bits of HTML.

Each one of these frames is a .htm file. Trying each of these one by one, it’s found that left.htm can always be accessed regardless of the login status. This is the left hand menu.

From here all of the menu items work fine (even if the individual .htm files didn’t work directly).

You can go to the “Password” page, view the source, and then recover the password and login normally.

This means that gaining remote access to these thermostats is as easy as going to:

http://87.56.123.121/left.htm

This is really not good.

Edit – the reason this happens is that the Javascript redirect (issue 8 below) has an error in it on left.htm…

Issue 8 – part of the authentication is Javascript based (up to v1.7)

Most of the thermostat pages have this little Javascript snippet on them:

if(document.logfm.lgst.value != "1")

top.location.href="index.htm";

This checks to see if you are logged in. If you aren’t, you get redirected back to the login page.

This would be a great idea if the same piece of HTML didn’t also include the content that you aren’t supposed to see.

You are letting the bad guys in regardless, and hoping you kick them out quickly enough not to see anything.

All you need to do to view the protected pages – including the one with the password in the open – is view the page in a browser with Javascript turned off, or use wget.

wget http://86.34.23.78/networkSetup.htm

This is amongst the most awful security design I have ever seen.

Issue 9 – commands are carried out by unauthenticated HTTP POST

Most people who use a web browser will be familiar with HTTP GET to send data to the server at the other end. Google queries are the most obvious:

https://www.google.co.uk/search?q=heatmiser+is+pwned

There is another mechanism called POST. You don’t see these in the URL like GET, but the idea is very similar.

All you need to do to change settings on the thermostat is send a POST request. No password required.

The barrier to entry here is that you can’t just type POST requests into the URL bar. But it isn’t exactly hard.

POST /statSetup.htm HTTP/1.1

Host: 70.129.58.10

User-Agent: Mozilla/5.0 (Macintosh; Intel Mac OS X 10.9; rv:32.0) Gecko/20100101 Firefox/32.0

Accept: text/html,application/xhtml+xml,application/xml;q=0.9,*/*;q=0.8

Accept-Language: en-US,en;q=0.5

Accept-Encoding: gzip, deflate

Referer: http://70.129.58.10/statSetup.htm

Connection: keep-alive

Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded

Content-Length: 32

setT=01%3A01&setD=01%2F01%2F2000

That’s just a grab from Burp Suite sending a request to a thermostat to change the time.

But you can seemingly change any setting.

Conclusion

I’ve stopped looking for issues at this point. There are probably a wealth of other things that could be worth investigating, including:

- Fuzzing the port 8068 input. Custom protocols are often vulnerable to malformed inputs causing crashes

- Hidden webpages

- Backdoor accounts

- Firmware inspection

But, at this point, it looks like security is the last thing on the list of priorities for Heatmiser.

If you want a thermostat that can’t be activated by just about anyone, then I would suggest returning your Heatmiser WiFi thermostat.

My recommendation would be to stop port-forwarding to both port 80 and 8068. You will lose remote control, but would still be able to access the thermostat from inside your house.

You can contact Heatmiser on [email protected] if you need help dealing with this.

Heatmiser’s response

I emailed Heatmiser to inform them of these issues.

I believe they must have been aware of some or all of these issues before now, and due to the severity and basic nature of the issues, I decided to follow full disclosure.

They have responded as follows:

Thank you for your email.

We are investigating the issues you mention and will provide an update to fix the security issues you highlight. We will advise customers in the meantime to close port 80 on their WiFi Thermostat until the issue has been rectified.

Once again, thank you for bringing this to our attention.

Heatmiser’s solution

Heatmiser have sent an email/letter out to customers. They have two options – replace the thermostat with one without a web interface and with rate limiting on the pin, or get a refund.

I’m surprised there is no attempt to fix the web interface.

Here is the Letter from Heatmiser sent out.